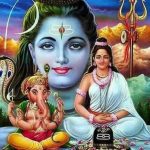

Most Hindu mythologies are built upon a logic of devotion (bhakti), connecting worship (puja), purity (shuddhi; sauca), morality (dharma), responsibility (karma), and austerities (tapas). Bhakti can be more than just “being religious,” since it can lead to liberation (moksha) from life’s addictions and even from the cycle of rebirth (samsara). This sense of liberation is often connected to an afterlife with a personal supreme god, such as Siva, Vishnu, or Devi. It has always involved a loving relationship with the divine. Some myths are told from the perspective of bhakti.

Indian philosophers and theologians began at least by the time of the Bhagavad Gita to classify religious or spiritual experience according to three or four types, which are called ways (margas) or disciplines (yogas). Bhakti appears in both lists. Devotionalism is the way (marga) or practice (yoga) known as bhakti marga or bhakti yoga.

Bhakti encompassed worship, prayers, and both elaborate and simple devotional rituals. But myths were not always linked to religious practice. Sometimes, devotion was a strategy of praise that was performed in order to gain power, a blessing, or a boon. What was gained by this kind of praise would then be used by the “hero” to complete his or her “quest,” or “pilgrimage.” This use of bhakti in these myths would be more a part of a world of magic or shamanism than of devotional spiritual practices.